Toxic traces - How environmental chemicals are changing our genes

Epigenetically active substances or genotoxic substances with direct DNA damage

The long-term effects of industrial pollution are not only physically measurable — they also leave traces in our biological heritage. Over the past two decades, it has become widely accepted that environmental toxins can cause epigenetic changes that are passed down through generations. Chemical substances such as heavy metals, solvents or hormone-active substances, e.g., bisphenol A, can influence epigenetic mechanisms, for example through DNA methylation (which alters the readability of genes without changing the DNA sequence) or histone modifications (which influence how genes are expressed). bisphenol A, can influence epigenetic mechanisms, for example through DNA methylation (which alters the readability of genes without changing the DNA sequence), histone modifications (which influence how tightly the DNA is packed and whether genes are active) or RNA-controlled processes. All of the substances listed here influence gene activity via reversible mechanisms such as DNA methylation, histone modification or RNA interference:

- Bisphenol A (BPA): Hormone-like, disrupts DNA methylation and histone acetylation.

- Phthalates: Endocrine disruptors, influence gene expression via histone modification.

- DDT: Alters epigenetic signatures, transgenerational effects.

- Arsenic: Inhibits DNA repair, alters methylation patterns.

- Cadmium: Influences histone modification, increases oxidative stress

- Mercury: Disrupts epigenetic regulation, neurotoxic

- Lead: Influences DNA methylation, especially during development

- Dioxins, e.g. TCDD: Activate epigenetic repressors, hormonal dysregulation

- Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): Disrupt gene expression via epigenetic pathways

- PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons): Induce epigenetic changes, carcinogenic

- Lindane (γ-HCH): Organochlorine compound, epigenetically and genotoxically active

- Vinyl chloride: CHC, carcinogenic and DNA-damaging

- PCP (pentachlorophenol): wood preservative, mutagenic and epigenetically active

- HCB (hexachlorobenzene): organochlorine compound, hormonally active

- Mineral oil residues: complex mixtures, contain PAHs and other genotoxic substances

- Chlorinated hydrocarbons (CHCs): e.g., trichloroethylene, tetrachloroethylene

- Benzene: known to increase the risk of leukemia, disrupts cell cycle regulation

- Formaldehyde: DNA cross-linking, carcinogenic

- Nitrosamines: formed, for example, during industrial combustion, mutagenic

Flood-induced release of pollutants

Many of these substances were also remobilized during flood events such as those in Dresden in 2002/2013. Suspended solids prior to the flood peak contained high concentrations of lead, arsenic and lindane. Sediment deposits in dyke forelands showed increased levels of DDT, PAHs, PCBs, and HCB and sewage treatment plant failures led to microbial contamination with antibiotic-resistant germs.

The GDR era was marked by the intensive and widespread use of chemical substances, in particular DDT (used in the GDR until the late 1980s), lindane (γ-HCH), benzene, arsenic, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and PAHs, pentachlorophenol (PCP) and many more. These substances were often used without adequate protective measures, resulting in chronic exposure for entire population groups. Many of these substances are now considered to have epigenetic and genetic effects. Research increasingly shows that toxic environmental influences not only cause acute damage, but also leave long-term traces in our genetic makeup and can be passed on across generations.

DDT and arsenic are two classic examples of environmental toxins that have been shown to cause genetic and epigenetic changes, sometimes even across generations. The long-term effects of environmental toxins such as dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) on our health are increasingly the focus of epigenetic and toxicological research. The risks are particularly high for people with genetic variants in methylation metabolism (e.g., MTHFR mutations), as their ability to repair and regulate genetic processes may be impaired. (Skinner MK et al. "DDT exposure, epigenetic transgenerational inheritance, and adult-onset disease." Reproductive Toxicology, 2013.)

Health-related perspectives

The combination of material and microbial pollution during flooding events poses a frequently underestimated risk to the long-term health and genetic integrity of already affected population groups, especially in areas that are regularly flooded, such as dyke forelands.

Hygiene issues and resistance problems

- Massive microbiological contamination due to the failure of sewage treatment plants

- Colonization of living spaces with antibiotic-resistant bacteria

- Potential epigenetic effects due to bacterial toxins and inflammatory processes

Between flooding, pollutants, and genetic risks

The Elbe flood of 2002 – chemical pollution documented

A study by Grunewald et al. (2004) examined 38 sampling sites along the Elbe River and its tributaries immediately after the 2002 floods. (46)

The study showed:

- Widespread distribution of pollutants due to flooding

- Substances with transgenerational, epigenetic, and hormonal effects

- Arsenic load of 10 tons, mobilized from contaminated sites, primarily from Muldenhütten near Freiberg

- PCB, PAH, and DDT concentrations with clear toxicological potential

- DDT: 1300 µg/kg TS in sample EL3 – 26 times above the test value of the BBodSchV (50 µg/kg TS for sensitive uses)

- PCB: up to 42 µg/kg TS (e.g. PCB-153)

- PAH: Benzo[a]pyrene up to 1.5 mg/kg DM

- Heavy metals: Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu, B – some significantly elevated

These data are precise, but they remain substance-centered, i.e., without reference to the biological effect on ourselves.

What does this mean for those with a genetic predisposition?

Source: Own representation

Genetic variants such as MTHFR, GST, COMT, APOE, MBL defect, PON1, and NAT2 alter the tolerance threshold: (48) - The “average toxicological limit” ignores genetic tolerance thresholds, i.e., individuals with a specific genetic makeup have completely different thresholds — often significantly lower.

Toxins do not act in isolation, i.e., a combination of genetics + chronic exposure + epigenetics determines the development of disease. It is important that studies integrate complex cascade models → not just measure concentrations. Environmental medicine should be interdisciplinary, i.e., environmental chemistry + molecular genetics + epigenetics + immunology, because this is the only way to identify long-term effects such as cancer, autoimmunity, infertility, or neurotoxicity.

Methodology for creating the extended pollutant overview in the context of the 2002 Elbe flood

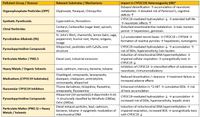

The pollutant table shown is based on a structured synthesis of three primary studies on sediment contamination resulting from the Elbe flood in 2002:

- Grunewald et al. (2004) – systematische Beprobung von 38 Standorten im Elbtal (z. B. Probenstelle EL3 bei Dresden), Grunewald, K. et al. (2004). Elbe flood 2002 in Retrospect: Pollution of sediments due to the extreme flood situation around Dresden. UWSF – Z Umweltchem Ökotox, 16(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1065/uwsf2004.02.073.

- Stachel et al. (2004/2005) – quantifizierte Analyse von organischen Schadstoffen, PCB-Kongeneren, Dioxinen und Sedimenttoxikologie. Stachel, B. et al. (2004). Occurrence of dioxin-like PCB in sediment and fish after the Elbe flood. Water Science & Technology, 50(5), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2004.0342. / Stachel, B. et al. (2005). Organic Contaminants in Sediment Samples Taken After the Elbe Flood. J Environ Sci Health A, 40(2), 265–287. https://doi.org/10.1081/ESE-200045531.

- Oetken et al. (2005) – ökologische Wirkung von kontaminierten Sedimenten anhand von Bioassays zur Reproduktion und Toxizität. Oetken, M. et al. (2005). Impact of a flood disaster on sediment toxicity in a major river system – the Elbe flood 2002 as a case study. Environmental Pollution, 134(1), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2004.08.001.

The substance groups listed in the table (e.g., PAHs, PCBs, pesticides, heavy metals, xenoestrogens) were taken directly from the studies mentioned or supplemented with scientifically documented congeners, provided that relevant evidence was available.

Data collection procedure

- The concentration data was either taken directly from the source or interpolated in the case of regional variations (median, maximum value, hot spot data).

- The substance groups were formed based on toxicological classifications according to IARC, IPCS/WHO, REACH regulations, and the toxicological units of German environmental authorities (UBA, LAUB, BBodSchV).

- Individual compounds such as p,p-DDT, benzo[a]pyrene, PCB-153, or arsenic were specified in their respective congener structures.

Addition of important toxicological effect categories

The “Toxicological effect” column is based on secondary research from internationally recognized toxicological data sources:

- IARC Monographs: Classification of substances according to carcinogenicity (Groups 1–3)

- IPCS/WHO: Data on substance properties such as persistence, bioaccumulation, hormonal activity

- TOXNET, PubChem, eChemPortal: molecular mechanisms of action, biochemical target structures

- Peer-reviewed studies on genetic modulation by GST-M1/T1, NAT2, MTHFR, SOD2, COMT, APOE, TLRs and immune markers

In doing so, I paid particular attention to the interaction with genetic vulnerability in order to gain a broader understanding of risk groups with detoxification deficits, immunological weaknesses or epigenetic instability.

Source: Own representation (July 8, 2025)

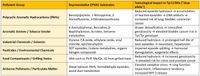

Relevance of environmental contaminants in NAT2 slow/ultra-slow acetylators

Methodology and sources used in compiling the tables

What does “ultra-slow” mean? You carry several NAT2 alleles with greatly reduced activity, e.g., *5, *6, *11, *12, *13 → ultra-slow acetylator. As a result, toxic amines remain in the body longer, bioactivation occurs instead of detoxification → formation of reactive metabolites and an increased risk of DNA damage, cancer, liver stress and much more.

This integrated table is based on a combined evaluation of toxicological literature, metabolism research and environmental analysis. I identified the substance groups from the following peer-reviewed primary sources and toxicological reviews:

- Hayes et al. (2005): Glutathione transferases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol

- Hein et al. (2008): NAT2 polymorphisms and carcinogen exposure. Toxicology

- Selinski et al. (2015): Ultra-slow acetylators enter the stage. Arch Toxicol

- Brans et al. (2004): NAT2 Genotyping. Clin Chem

- Green et al. (2000): NAT2 and bladder cancer. Br J Cancer

- Rodrigues-Lima et al. (2008): Effect of chemicals on NAT2 activity. Curr Drug Metab

- Turesky & Le Marchand (2011): HAA metabolism and cancer risk. Adv Mol Toxicol

- Figueroa et al. (2014): NAT2 and bladder cancer risk. CEBP

- Risch et al. (1995): 4-ABP and NAT2 genotype synergy. Cancer Epidemiol

- Wikipedia Contributors (2024): N-acetyltransferase 2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/N-acetyltransferase_2.

Procedure

- Substances were grouped according to structural similarity and known NAT2 affinity.

- I classified individual substances based on their documented metabolism by NAT2.

- The toxicological effects are based on molecular biological studies (including DNA adduct formation, ROS generation, epigenetic dysregulation).

- Environmental relevance was linked to real sources of exposure (food, smoke, industry).

Source: Own representation (July 8, 2025)

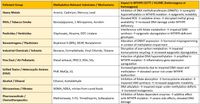

Relevance of environmental contaminants in the context of GST-M1/T1/P1 polymorphisms

Methodology and sources used for the GST table - (49) (50) (51) (52)

This table is based on a structured evaluation of the following primary scientific sources

- Hayes et al. (2005): Glutathione transferases. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology

- Hein et al. (2008): GST polymorphisms and environmental exposure to carcinogens. Toxicology

- Suthar et al. (2017): GST-M1/T1 activity and substrate specificity. IJPSR https://ijpsr.com/bft-article/glutathione-s-transferases-a-brief-on-classification-and-gstm1-t1-activity/.

- Hellou et al. (2012): GST and oxidative stress biomarkers in aquatic biota. Environmental Science and Pollution Research https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11356-012-0909-x.

- Genetic Lifehacks (2025): GSTM1 and environmental toxins https://www.geneticlifehacks.com/gst-glutathione-detoxification/.

- Wikipedia Contributors (2024): Glutathione S-transferase https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glutathione_S-transferase.

Procedure

- I assigned the substrates based on documented GST affinity (primarily GST-M1, GST-T1, GST-P1).

- The toxicological effects were derived from molecular biological studies on ROS, DNA adducts, enzyme inhibition, and epigenetic dysregulation.

- The sources of exposure were supplemented here in a realistic manner (tobacco smoke, barbecue food, pesticides, industrial chemicals, pharmaceuticals).

- I created this table in a similar way to the NAT2 matrix in order to present genetic detoxification weaknesses in a comparable way.

Source: Own representation (July 8, 2025)

I also consider microsomal epoxide hydrolase 1 (EPHX1) to be highly relevant here, as it plays a central role in phase I detoxification, particularly in the bioactivation and detoxification of epoxides produced from PAHs, aromatic amines, tobacco smoke, solvents and industrial chemicals. The polymorphism variant in exon 3 (Tyr113His) significantly influences enzyme activity:

Tyr113 (wild type) → normal activity

His113 (mutant) → up to 50% reduced enzyme activity → so-called “slow allele”

Relevance of environmental contaminants in the context of EPHX1 exon 3 (Tyr113His)

Methodology and sources

This table is based on a structured evaluation of the following primary scientific sources

- Taha et al. (2021): Association of EPHX1 exon 3 polymorphism with lung function in wood workers https://doi.org/10.1515/jcim-2020-0085.

- Taha et al. (2021): Antioxidant status in EPHX1 slow/fast alleles https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14166-0.

- Václavíková et al. (2015): EPHX1 polymorphisms and cancer susceptibility – [PubMed]

- Hassett et al. (1994): Functional characterization of EPHX1 exon 3/4 variants – [J Biol Chem]

- Gautheron & Jéru (2021): The Multifaceted Role of Epoxide Hydrolases in Human Health and Disease. https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/22/1/13.

- Perucca (2005): Clinically relevant drug interactions with antiepileptic drugs. https://bpspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02529.x.

- EPXH1 Gene - Gene Card, https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=EPHX1.

- PharmGKB (2025): Omeprazole and Esomeprazole Pathway. https://www.pharmgkb.org/pathway/PA152530846.

- Wikipedia Contributors (2024): Microsomal epoxide hydrolase – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microsomal_epoxide_hydrolase.

Procedure

- I assigned the substrates based on documented EPHX1 affinity (primarily for PAHs, aromatic amines, epoxides).

- I derived the toxicological effects from molecular biological studies on DNA adducts, ROS, enzyme inhibition, and inflammatory mediators (MIP-2).

- I also constructed this table in the same way as NAT2 and GST Matrix in order to present genetic detoxification weaknesses in a comparable manner.

Source: Own representation (July 8, 2025)

The variant EPHX1 c.337T>C (according to HGVS nomenclature) leads to an amino acid substitution from tyrosine to histidine in the protein, i.e. p.Tyr113His. 337T>C refers to the nucleotide position in the cDNA (codon 113). Tyr113His is the protein change: tyrosine (Y) is replaced by histidine (H) at position 113.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/16604/

Source: genetic predisposition

It is also very important to address the clinically highly relevant interface between pharmacogenetics, environmental medicine, and drug tolerability here. The combination of EPHX1 polymorphism (e.g., Tyr113His / rs1051740) and other genetic detoxification deficits (e.g., GST-M1/T1-null, NAT2 ultra-slow) can lead to massive problems with the tolerability of epoxide-containing drugs and thus to severe drug-drug interactions (DDIs).

Medicines containing epoxide metabolites – particularly critical in the case of the EPHX1 slow genotype

Source: Own representation (July 8, 2025)

Clinical consequences

DDIs (drug–drug interactions)

- EPHX1-Slow → reduced epoxide hydrolysis → toxic metabolites remain longer

- Combination with CYP inducers (e.g., phenobarbital) → Overproduction of epoxides that cannot be broken down

- Consequence: neurotoxic, hepatotoxic, and immunological side effects

PGX test results (pharmacogenetics)

- Intolerance to carbamazepine, allopurinol, phenytoin and phenobarbital can be explained at the molecular level.

- Particularly critical when combined with environmental toxins (PAHs, DDT, PCBs), which are also metabolized via EPHX1.

Synergy with environmental impact

- With simultaneous exposure to, for example, PAHs from tobacco smoke or particulate matter → massive toxic accumulation

- EPHX1 slow + GST-M1/T1 null + NAT2 ultra-slow = maximum vulnerability

Note on omeprazole and lansoprazole: Metabolized as prodrugs via CYP2C19/CYP3A4 – their sulfoxide and hydroxy metabolites can be problematic in cases of genetically impaired detoxification, especially when combined with GST or EPHX1 deficiency.

Source: PGx surveys / genetic predisposition

Relevance of environmental contaminants in the context of disrupted DNA methylation by MTHFR C677T / A1298C

Genetic variants MTHFR C677T and A1298C are central switching points in the folate cycle and have profound effects on DNA methylation, epigenetic regulation and thus on cellular stress response, detoxification, immune function and cancer susceptibility. (47)

Mechanism: MTHFR → SAM → DNA methylation

- MTHFR converts 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate (5,10-THF) to 5-methyl-THF → essential for the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine

- Methionine → precursor of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) → universal methyl group donor

- In C677T (Val/Val): Enzyme activity ↓ up to 70% → SAM ↓ → global hypomethylation

- In A1298C (Glu/Ala): Enzyme activity ↓ by approx. 40% → synergistic with C677T → epigenetic dysregulation

Sources

- Fernández-Peralta et al. (2010): MTHFR polymorphisms and epigenetic characteristics of tumors –https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00384-009-0779-y.

- Ferlazzo et al. (2017): Influence of MTHFR on p16 and MGMT methylation in oral cancer – https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/18/4/724.

- Yadav et al. (2021): MTHFR C677T, global DNA methylation and hypertension – https://bmcmedgenomics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12920-021-00895-1.

- He et al. (2024): Combined effect of MTHFR C677T and A1298C on digestive system cancer – https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12672-024-00960-y.

- Wikipedia Contributors (2024): Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Methylenetetrahydrofolate_reductase.

Source: Own representation (July 8, 2025)

Relevance of environmental stressors in the context of COMT rs4680 (Val158Met)

The COMT rs4680 polymorphism (Val158Met) is a key genetic marker for stress processing, dopamine regulation, and reactivity to environmental stressors. The variant mentioned above influences the activity of the enzyme catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), which is responsible for the breakdown of dopamine, norepinephrine and epinephrine — especially in the prefrontal cortex.

Genotypic classification

- rs4680 A/A (Met/Met) → reduced COMT activity (~25% of wild-type activity) → “worrier” type: elevated dopamine levels, increased response to stress, pain and environmental stimuli

- rs4680 G/G (Val/Val) → normal COMT activity → “Warrior” type: better stress resistance, but lower cognitive flexibility

- rs4680 A/G (Met/Val) → intermediate activity

Sources

- Crum et al. (2018): COMT moderates effect of stress mindset on affect and cognition. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195883.

- SelfHacked (2024): COMT rs4680 and environmental stress response. https://selfhacked.com/blog/worrier-warrior-explaining-rs4680comt-v158m-gene/.

- SNPedia (2024): rs4680 functional annotation. https://www.snpedia.com/index.php/Rs4680.

- PlexusDx (2025): COMT rs4680 and cognitive stress resilience. https://plexusdx.com/blogs/learn/effects-of-comt-gene-variant-rs4680-on-stress-resilience-and-cognitive-abilities.

- Hall et al. (2015): COMT genotype and placebo response. [PMID: 25962166]

Source: Own representation (July 8, 2025)

Relevance of environmental contaminants and drugs in the context of CYP2C19 rs4244285 (2-HET)*

CYP2C19, especially 2-heterozygosity (rs4244285),* is not only crucial for pharmacotherapy, but also for the detoxification of numerous environmental contaminants, especially pesticides, plant substances and industrial chemicals.

Genetic classification: CYP2C19 rs4244285 (*2)

- rs4244285 (G>A) → aberrant splice site → loss of function

- Heterozygous (1/2)** → intermediate metabolizer (IM)

- Homozygous (2/2)** → poor metabolizer (PM)

Clinical relevance (excerpts)

- Clopidogrel: reduced activation → increased risk of thrombosis

- Omeprazole: prolonged half-life → side effects ↑

- Allopurinol: Accumulation → Hypersensitivity, DRESS syndrome

Genetic synergies with other detox polymorphisms

- CYP1A1 rs1048943 Phase I oxidation of PAHs → in case of mutation: increased bioactivation of toxic metabolites

- CYP3A5 rs776746 Metabolism of steroids, immunosuppressants → in case of *3: reduced activity

- NAT2 rs179993 Acetylation of aromatic amines → in ultra-slow: prolonged toxicity

- PON1 rs662 Detoxification of organophosphates → in Q192R: reduced hydrolysis activity

- ABCB1 rs1045642 / rs1128503 Transporter for drugs and xenobiotics → in case of mutation: impaired efflux function

Sources

- Vignaux et al. (2023): CYP2C19 inhibition by organophosphate pesticides. Chem Res Toxico https://europepmc.org/article/MED/37650603

- Windholz 1983a, Ochs 2002a – UZH-Wirkstoffdatenbank, Allopurinol als Pyrazolopyrimidin: Chemisch klassifiziert als 1H-pyrazolo(3,4-d)pyrimidin-4-ol https://www.vetpharm.uzh.ch/Wirkstoffe/000000000031/5300_01.html., besonders relevant da diese klinisch und toxikologisch essenziell sind und die Verbindung zwischen Umweltbelastung, genetischer Detoxifikation und epigenetischer Regulation verdeutlichen.

- Clinical Epigenetics – Ferrari et al. (2019), PM2.5-induzierte mitochondriale DNA-Hypermethylierung: Feinstaub führt zu epigenetischen Veränderungen der mtDNA, insbesondere in MT-TF und MT-RNR1, https://clinicalepigeneticsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13148-019-0726-x., besonders relevant da diese klinisch und toxikologisch essenziell sind und die Verbindung zwischen Umweltbelastung, genetischer Detoxifikation und epigenetischer Regulation verdeutlichen.

- SNPedia (2024): rs4244285 functional annotation. https://www.snpedia.com/index.php/Rs4244285.

- Hirota et al. (2023): Impact of CYP2C19 polymorphisms on drug metabolism. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/dmpk/28/1/28_DMPK-12-RV-085/_pdf.

- EFSA (2020): Pyrrolizidine alkaloids in food and herbal products. https://www.ages.at/en/human/nutrition-food/residues-contaminants-from-a-to-z/pyrrolizidine-alkaloids.

- Schrenk et al. (2021): Genotoxicity of pyrrolizidine alkaloids. https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/pdf/10.1055/a-1646-3618.pdf.

- PharmGKB (2025): CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics overview. https://www.pharmgkb.org/vip/PA166169770.

- DocCheck Flexikon (2024): CYP2C19 substrates & interactions. https://flexikon.doccheck.com/en/CYP2C19.

- EPA Indoor VOC Reports / ESIG Technical Guidance on VOCs / AGES Österreich: Altlastenanalytik & Chlorierte Lösungsmittel / EFSA: Pyrrolizidinalkaloide in Gebäuden (z. B. Kamille, Melisse)

Source: Own representation (July 8, 2025)

The current presentation refers to the effect of individual drugs in the context of CYP2C19 genotyping (here monotherapy + ABCB1 transporter (shown as an exclamation mark)), but there are many other additional factors that influence corresponding DDIs in CYP2C19 variants. In this case, it is strongly recommended to perform a PGx report extension for a realistic drug evaluation and to expand the CYP2C19-based monotherapy analyses with the following modules:

- Polypharmacy dosage check: combination of several CYP substrates/inhibitors

- Environmental health risk profile: exposure to pesticides and pollutants

- Neurohormonal influence analysis: stress axes, gender, hormonal therapies

- Immunogenetic risk panel: HLA, EBV reactivation, interleukin profiles

- Transporter functionality: ABCB1, SLC gene analyses

Source: Personas' own representations

Genetic markers and enzymes

Source: Own representation (July 8, 2025)

Transporter families and their function

Sources: Own representation (July 8, 2025)

ABC transporters are present in all living organisms – from bacteria to humans. Their activity is based on ATP hydrolysis, which triggers conformational changes and actively transports substrates across the membrane. They typically consist of two transmembrane domains (TMDs) and two ATP-binding domains (NBDs). P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) was first discovered in 1976 and remains one of the most important markers for drug resistance and environmental barrier function.

OAT1 (SLC22A6) Kidney, choroid plexus Antibiotics, prostaglandins, indoxyl sulfate, heavy metals

OAT2 (SLC22A7) Liver, kidney Salicylate, cGMP, antiviral drugs

OAT3 (SLC22A8) Kidney, brain, retina Conjugated steroids, vitamins, plant toxins

OAT4 (SLC22A11) Placenta, kidney Estrone sulfate, urates, ochratoxin A

OATPs (SLCO family) Liver, intestine, brain Transport of larger anionic substrates such as statins, hormones, drugs

Quellen

- Nies, A. T., Koepsell, H., Damme, K., & Schwab, M. (2011). Organic Cation Transporters (OCTs, MATEs), In Vitro and In Vivo Evidence for the Importance in Drug Therapy. In: Fromm, M.F., Kim, R.B. (eds) Drug Transporters, Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, vol 201. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-14541-4_3.

- Volk, C. (2014). OCTs, OATs, and OCTNs: Structure and Function of the Polyspecific Organic Ion Transporters of the SLC22 Family. WIREs Membr Transp Signal, 3(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/wmts.100.

- Wu, C., Chakrabarty, S., Jin, M., Liu, K., & Xiao, Y. (2019). Insect ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) Transporters: Roles in Xenobiotic Detoxification and Bt Insecticidal Activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(11), 2829. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20112829.

- Engelhart, D., Granados, J. C., Shi, D., Saier Jr., M., Baker, M., Abagyan, R., & Nigam, S. K. (2019). Reclassification of SLC22 Transporters: Analysis of OAT, OCT, OCTN, and other Family Members Reveals 8 Functional Subgroups. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.23.887299.

- Motohashi, H., & Inui, K. (2013). Organic Cation Transporter OCTs (SLC22) and MATEs (SLC47) in the Human Kidney. The AAPS Journal, 15(2), 581–588. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-013-9465-7.

- Rismondo, J., & Schulz, L. M. (2021). Not Just Transporters: Alternative Functions of ABC Transporters in Bacillus subtilis and Listeria monocytogenes. Microorganisms, 9(1), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9010163.

Environmental parameters, substance classes, PGx

Source: Own representation (July 8, 2025)

Systemic factors influencing DDIs and environmental toxicity

Source: Own representation (July 8, 2025)

Indoor air pollution in buildings at risk of flooding

Lipophilic VOCs and chlorinated solvents – indoor pollution caused by lipophilic and water-reactive pollutants after flooding

Overview of potentially critical substance classes in indoor spaces after flooding

This chapter contributes to the early detection of toxic indoor pollution and may be used in the context of official remediation planning or health precautions.

Source: Own representation (July 8, 2025)

Toxicological characteristics after flooding

- Lipophilic substances can be released in damp buildings from old sealants, wall materials and storage residues.

- How does chloropicrin get into our basements and shafts? Contaminants from construction chemicals and wood preservation: Chloropicrin was previously used as an antimicrobial wood preservative, e.g., in support beams, basement ceilings, pipe shafts, or utility carriers. → When exposed to moisture or thermal stress (e.g., flooding, fire), it can outgas and accumulate in poorly ventilated areas. Release from insulation and sealants: In older buildings, chlorinated solvents such as chloropicrin were used as additives in sealants, adhesives, or insulation materials. → After moisture penetration or material decay (e.g., due to mold or chemical reaction), chloropicrin can enter the indoor air. Secondary contamination through storage or remediation: Pesticides, wood preservatives or technical chemicals were previously stored in basements — often without proper disposal. → These substances can be reactivated and released in the event of flooding or improper remediation. Persistence and indoor accumulation: Chloropicrin is highly volatile, but also lipophilic – it can accumulate in porous materials such as concrete, wood, or insulation materials and be released slowly. → This is particularly critical in crawl spaces, utility shafts, and cavities where there is no air circulation. (69) (70) (71) (72)

- In closed rooms with poor ventilation, they can accumulate near the floor.

- Absorption occurs through the skin, mucous membranes and respiratory trac t— often with delayed symptoms.

Why is it toxicologically relevant?

- Chloropicrin irritates the eyes, respiratory tract, and skin, can cause pulmonary edema and is mutagenic in laboratory experiments.

- Absorption occurs through inhalation and the skin, often with delayed symptoms.

- People with PGx polymorphisms in GSTM1, CYP2E1, EPHX1, SOD2, and COMT — i.e., those with a limited ability to detoxify chlorinated VOCs — are particularly at risk.

Some typical representatives and their genetic relevance

- Chlorinated VOCs / trichloroethylene, chloropicrin, tetrachloroethylene → detoxification via GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1, CYP2E1, NAT2, EPHX1, SOD2, COMT

- Organophosphates / Paraquat, Chlorpyrifos, Glyphosate → PGx relevance via CYP2C19, PON1, NAT1, ABCB1, UGT2B15

- Lipophilic plant toxins / formaldehyde, acrolein, crotonaldehyde → risk associated with ADH5, ALDH2, GSTA1, GSTP1, NQO1 polymorphisms

- Nitrogen compounds / Anilines (C₆H₅NH₂), o-toluidine (2-methylaniline), nitro compounds, e.g., nitrobenzene, trinitrotoluene / These aromatic amines and nitroaromatics are known for their carcinogenic potency, particularly in connection with bladder cancer and oxidative stress. They are produced, among other things, in industrial processes, fires, contaminated sites, or through release from contaminated materials. → Critical in SULT1A1 (sulfotransferase – phase II enzyme for the conjugation of aromatic amines), NAT2 slow (N-acetyltransferase – slow acetylators show increased toxicity to anilines and o-toluidine), UGT1A1 (UDP-glucuronosyltransferase – important for the glucuronidation of aromatic nitrogen compounds), EPHX1 variants (epoxide hydrolase – relevant for the detoxification of reactive epoxides formed from nitro compounds) (66) (67) (68)

- Lipophilic neurotoxins, e.g., VX-like substances → detoxification pathways often unknown, partially reduced in PON1, CYP2C9, GSTs, FMO3 polymorphisms

“Lipophilic substances accumulate in cell membranes and are particularly critical in polymorphisms of phase I/II enzymes.” → “Long-term risk from poorly degradable lipophilic environmental pollutants in indoor spaces”

Some of the substances mentioned are not only found in civilian contaminated sites, but are also known as residues from military use. Their toxicological effect is independent of their origin – the decisive factor is the individual's detoxification capacity. The combination of lipophilic persistence, poor ventilation, and genetic detoxification weakness can lead to delayed but serious symptoms, especially in individuals with PGx-relevant polymorphisms.

Please note the many sensitive groups of people and why toxicogenetic environmental profiles are essential in the event of flooding and fires (see section “Silent Cargo”).

Environmental Sensitivity Profiles – Environmentally Sensitive Groups of People – Risk Profiles

Why toxicogenetic environmental profiles are essential in the event of flooding and fires

Bibliography and list of sources (accessed on July 1, 2025)

(1) TAG24. (2021, 9. Dezember). Tschüss Uran-Abbau: Die letzte strahlende Fuhre geht in die USA. https://www.tag24.de/sachsen/tschuess-uran-abbau-die-letzte-strahlende-fuhre-geht-in-die-usa-1986245

(2) Wismut GmbH. (2017). Sanierung des Uranbergbaus in Sachsen – Stand und Perspektiven. Berg- und Hüttenmännische Monatshefte, 162(11), 478–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00501-017-0643-2.

(3) Bing. (2025). Zellstoffwerke DDR Firmen Elbe Schadstoffe. https://www.bing.com/search?q=Zellstoffwerke+DDR+Firmen+Elbe+Schadstoffe&toWww=1&redig=D6F5FA20E440452292FBA764990D743E

(4) FS-Journal. (o. J.). Schadstoffe in der Elbe – Messprogramm von der Quelle bis zur Mündung. https://fs-journal.de/forschung-und-entwicklung/schadstoffe-in-der-elbe-messprogramm-von-der-quelle-bis-zur-muendung/

(5) Umweltbundesamt. (2024). Schadstoffbericht 2024 – Textteil und Steckbriefe 2024_Schadstoffbericht_Textteil_und_Steckbriefe.pdf

(6) Landeshauptstadt Dresden. (2003). Elbehochwasser 2002 – Dokumentation, Elbehochwasser2002.pdf

(7) Bundesanstalt für Gewässerkunde (BfG). (2002). Das Sommerhochwasser 2002 im Elbegebiet – Stoffliche Belastung. https://undine.bafg.de/elbe/extremereignisse/elbe_hw2002.html

(8) Hübler, M. (2014). Altlasten und Hochwasser – ein unterschätztes Risiko? In M. Hübler (Hrsg.), Altlasten – Risiken erkennen und bewältigen (S. 123–140). Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-658-06173-9_6.

(9) Verband Wohneigentum Sachsen e. V. (o. J.). Rückblick Hochwasser Pirna 2002. https://www.verband-wohneigentum.de/sv-pirna1/on57393.

(10) Wikipedia. (2025). Hochwasser in Mitteleuropa 2002. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hochwasser_in_Mitteleuropa_2002.

(11) Internationale Kommission zum Schutz der Elbe (IKSE). (2003). Dokumentation des Hochwassers vom August 2002 im Elbegebiet [Printausgabe].

(12) Bundesanstalt für Gewässerkunde (BfG). (2003). Stoffliche Belastung der Elbe durch das Hochwasser 2002 [Printausgabe].

(13) Wismut GmbH. (2005). Sanierungsbericht Königstein 2002–2005 [nicht online verfügbar, in Fachbibliotheken einsehbar].

(14) Bundesanstalt für Gewässerkunde (BfG). (2002). Das Sommerhochwasser 2002 im Elbegebiet – Stoffliche Belastung. https://undine.bafg.de/elbe/extremereignisse/elbe_hw2002.html.

(15) AGÖF. (2006). VOC-Datenbank [interne Datenbank, nicht öffentlich zugänglich].

(16) Umweltbundesamt & AGÖF. (2004). Orientierungswerte für VOC in Innenräumen [Printveröffentlichung].

(17) Stadt Dresden. (2003). Interne Berichte zur Raumluftqualität in überfluteten Gebäuden [nicht öffentlich zugänglich, in Fachkreisen zitiert].

(18) Grunewald, K., Unger, C., Brauch, H.-J., & Schmidt, W. (2004). Elbehochwasser 2002 – Schadstoffbelastung von Schlamm- und Sedimentproben im Raum Dresden. UWSF – Umweltchemie und Ökotoxikologie, 16(1), 7–14. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Karsten-Grunewald/publication/240953387_Elbe_flood_2002_in_Retrospect_Pollution_of_sectiments_due_to_the_extreme_flood_situation_around_Dresden_Saxony_Germany_Schadstoffbelastung_von_Schlamm-_und_Sedimentproben_im_Raum_Dresden_Sachsen/links/00b4952170f0966a94000000/Elbe-flood-2002-in-Retrospect-Pollution-of-sectiments-due-to-the-extreme-flood-situation-around-Dresden-Saxony-Germany-Schadstoffbelastung-von-Schlamm-und-Sedimentproben-im-Raum-Dresden-Sachsen.pdf.

(19) Universität Hamburg. (2015). Fachstudie Elbauenböden – ELSA-Projekt. https://elsa-elbe.de/massnahmen/fachstudien-neu/fachstudie-elbauenboeden.html.

(20) Umweltbundesamt. (2003). Stoffliche Belastung der Elbe durch das Hochwasser 2002 [Printveröffentlichung].

(21) Hübler, M. (2022). Altlasten und toxikologische Risiken bei Extremhochwasser. In M. Hübler (Hrsg.), Umweltgefahren im Klimawandel (S. 211–230). Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-658-46760-9_9

(22) Hübler, M. (2020). Altlastenmanagement und Bevölkerungsschutz. In M. Hübler (Hrsg.), Umweltmedizin im Einsatz (S. 33–52). Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-658-26743-8_2

(23) Landeshauptstadt Dresden. (2022, 12. Dezember). Pressemitteilung: 20 Jahre nach dem Hochwasser 2002. https://www.dresden.de/de/rathaus/aktuelles/pressemitteilungen/2022/12/pm_036.php?pk_kwd=news.

(24) Kachelmannwetter. (2017). Vor 15 Jahren: Hochwasser der Elbe. https://wetterkanal.kachelmannwetter.com/vor-15-jahren-hochwasser-der-elbe/

(25) Der Spiegel. (1981, 25. Mai). Die Elbe ist meilenweit biologisch tot [Spiegel-Ausgabe Nr. 22]. Der Spiegel schrieb 1981: > „Die Elbe ist meilenweit biologisch tot: Fische mit Schwermetallen vergiftet, dürfen nicht mehr in den Handel, tonnenweise krepieren sie wegen Sauerstoffmangels im Fluss. […] Proteste gegen den Dreck in der ‚Kloake der Industrie‘ bewirken wenig.“ https://www.altezeitschriften.de/der-spiegel/230-der-spiegel-nr22-25-mai-1981.html

(26) Landeshauptstadt Dresden. (2025, 30. Juni). Pressemitteilung: 4,8 Mio. Euro Fördermittel für Sanierung Rosenstraße 77. https://www.dresden.de/de/rathaus/aktuelles/pressemitteilungen/06/pm_096.php

(27) Landeshauptstadt Dresden. (2025). Sanierungsprojekt Rosenstraße 77. https://www.dresden.de/de/stadtraum/umwelt/umwelt/boden/altlasten/sanierung-rosenstrasse77.php

(28) Bundesministerium für Umwelt. (2009). Richtlinie zum Management von Hochwasserrisiken (PDF-Dokument: richtlinie_management_hochwasserrisiken.pdf)

(29) Wikipedia. (2025). Richtlinie 2007/60/EG über die Bewertung und das Management von Hochwasserrisiken. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richtlinie_2007/60/EG_%C3%BCber_die_Bewertung_und_das_Management_von_Hochwasserrisiken

(30) Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF). (2025). Nachhaltiges Wassermanagement – Forschung für Nachhaltigkeit. https://www.bmbf.de/DE/Forschung/EnergieKlimaUndNachhaltigkeit/ForschungFuerNachhaltigkeit/NachhaltigesWassermanagement/nachhaltigeswassermanagement_node.html

(31) Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung (UFZ). (2025). Forschung zu Altlasten & Hochwasserfolgen. https://www.ufz.de/index.php?de=35789

(32) ME/CFS Research Foundation. (2024). Cost Report: Long Covid and ME/CFS – Economic burden & care gap analysis. https://mecfs-research.org/costreport-long-covid-and-mecfs/.

(33) Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (BMG). (2023). Studie Charité & Max Delbrück Center: Erkenntnisse zu ME/CFS bei Long Covid. https://www.bmg-longcovid.de/zeitstrahl/studie-charite-max-delbrueck-center-erkenntnisse-me-cfs.

(34) Long Covid Plattform. (2024). ME/CFS: Chronisches Fatigue-Syndrom im Kontext von Long Covid. https://www.long-covid-plattform.de/me-cfs.

(35) Lost Voices Stiftung. (2023). Zusammenhang zwischen Long Covid und ME/CFS. https://lost-voices-stiftung.org/zusammenhang-zwischen-long-covid-und-me-cfs/.

(36) Ziyad Al-Aly, 2024, Ziyad Al-Aly is director of research and development at the VA St. Louis Health Care System and a clinical epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis, CBS News, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/long-covid-what-scientists-now-know/ (accessed Sept. 28, 2024)

(37) Pam Belluck, 9.8.2024, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/09/health/long-covid-world.html (accessed: 31.08.2024)

(38) Britta Domke, 16.05.2024, Manager Magazin, https://www.manager-magazin.de/lifestyle/long-covid-konferenz-wir-muessen-uns-endlich-eingestehen-wie-gewaltig-dieses-problem-ist-a-4389644b-1795-4acf-bccf-759d6dce1982 (accessed: 31.08.2024)

(39) Proplanta Agrar-Nachrichten. (2015, 7. November). DDR-Altlasten: Noch rund 1.000 Flächen belastet – Sanierungsbedarf in Sachsen-Anhalt bleibt hoch. https://www.proplanta.de/agrar-nachrichten/umwelt/ddr-altlasten-noch-rund-1-000-flaechen-belastet_article1446902833_s14468961244_seite_2.html (Abgerufen am 3. Juli 2025)

(40) Ministerium für Wissenschaft, Energie, Klimaschutz und Umwelt Sachsen-Anhalt (MWU). (2025). Altlastenmanagement und Bodenschutz im Land Sachsen-Anhalt – Maßnahmen, Strategie, rechtliche Grundlagen. https://mwu.sachsen-anhalt.de/umwelt/bodenschutz/altlasten (Abgerufen am 3. Juli 2025)

(41) Die Welt. (2015, 6. November). In Sachsen sind 9.000 Hektar ehemals belasteter Flächen saniert – Umweltministerium zieht Zwischenbilanz. https://www.welt.de/regionales/sachsen/article148552141/In-Sachsen-sind-9000-Hektar-ehemals-belasteter-Flaechen-saniert.html. (Abgerufen am 3. Juli 2025)

(42) Medienservice Sachsen. (2015, 6. November). Sachsen: Rund 9.000 Hektar Altlastenflächen erfolgreich saniert – Umweltminister Schmidt lobt nachhaltige Förderstruktur. https://www.medienservice.sachsen.de/medien/news/199144. (Abgerufen am 3. Juli 2025)

(43) EUWID Recycling & Entsorgung. (2024, 2. Februar). Altlastensanierung Sachsen: Über 40 Millionen Euro Fördermittel bis 2027 – EFRE und Landesmittel im Überblick. https://www.euwid-recycling.de/news/politik/altlastensanierung-in-sachsen-wird-mit-ueber-40-mio-eur-gefoerdert-020224/. (Abgerufen am 3. Juli 2025)

(44) Rosner, S., Herrmann, R., Schellenberger, A., & Richter, B. (2017). Sicherung und Verwahrung von uranvererzten Bergbauhalden innerhalb einer Mischaltablagerung in Dresden-Coschütz – Collmberghalde Langfassung. BAUGRUND DRESDEN Ingenieurgesellschaft mbH & IAF Radioökologie GmbH. https://www.baugrund-dresden.de/files/publikationen/2017/fachsektionstage_collmberghalde_.pdf. (Abgerufen am 3. Juli 2025)

(45) Wismut GmbH. (2024, April). Sanierung der Collmberghalde in Dresden-Coschütz – Altlastenprojekt mit radiologischer Relevanz. In DIALOG – Zeitschrift der Wismut GmbH, Ausgabe 122, S. 16–17. https://www.wismut.de/fileadmin/user_upload/PDF/Dialog_Ausgaben/Wi-Dialog-122_web.pdf. (Abgerufen am 3. Juli 2025)

(46) Grunewald, K., Unger, C., Brauch, H.-J., & Schmidt, W. (2004). Elbe flood 2002 in Retrospect: Pollution of sediments due to the extreme flood situation around Dresden (Saxony, Germany). In: Umweltwissenschaften und Schadstoff-Forschung (UWSF), 16(1), 7–14.

(47) Peerbooms, O. et al. (2012). COMT & MTHFR interaction moderates stress response. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 125(3), 247–256. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01806.x

(48) Stachel, B. et al. (2004). Occurrence of dioxin-like PCB in sediment and fish. Water Sci Technol, 50(5), 309–316. https://iwaponline.com/wst/article/50/5/309/11400/The-Elbe-flood-in-August-2002-occurrence-of.

(49) Ganz immun diagnostics, Laborhandbuch zu GST-M1/T1/P1, https://www.ganzimmun.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Glutathion-S-Transferase-Gene_M1__T1_und_P1_LIN0054_001.pdf.

(50) Hayes, J. D., Flanagan, J. U., & Jowsey, I. R. (2005). Glutathione transferases. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 45, 51–88. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857. Bedeutung für die Konjugation elektrophiler Stoffe wie Polyzyklische aromatische Kohlenwasserstoffe (PAK) und chlororganische Verbindungen (z. B. PCB)

(51) Strange, R. C., Spiteri, M. A., Ramachandran, S., & Fryer, A. A. (2001). Glutathione-S-transferase polymorphisms: influence on susceptibility to oxidative stress and carcinogens. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis, 482(1–2), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0027-5107(01)00227-X. GST-M1/T1-Null-Typen zeigen verminderte Fähigkeit, PCB-Metabolite zu entgiften

(52) Bolt, H. M., Thier, R., & Pesch, B. (2006). Glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms and environmental exposure to carcinogens. Toxicology, 221(2–3), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2006.01.015. Bewertung der Detox-Funktion bei GST-M1/T1-Null-Genotypen. Betont die Wichtigkeit dieser Gene bei metabolischer Elimination von PAK und chlororganischen Stoffen.

(53) J. Liu et al. (2021): Urinary heavy metal concentrations and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children Journal of Attention Disorders, Vol. 25(14), pp. 2028–2036 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054721996611.

(54) Xu et al. (2022): Prenatal exposure to heavy metals and neurodevelopmental disorders in children: A systematic review Environmental Research, Volume 210, Article 112921 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.112921.

(55) C. Zhang et al. (2023): Association between lead exposure and behavioral problems in school-age children Neurotoxicology, Volume 94, pp. 64–72 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2022.10.008.

(56) D. Bellinger (2019): Prenatal and early childhood exposure to lead and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes Pediatrics, 144(5), e20193893 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-3893.

(57) SNPedia – COMT Val158Met polymorphism: Einfluss auf Dopaminabbau und Reizverarbeitung bei ADHS Link: https://www.snpedia.com/index.php/Rs4680.

(58) E. Volz et al. (2017): Gene–Environment interactions in ADHD: Effects of MAOA and environmental adversity Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(12), pp. 1321–1329 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12739.

(59) Molnar et al. (2024): Mitochondrial dysfunction in long COVID: mechanisms, consequences, and potential therapeutic approaches GeroScience, 46, 5267–5286 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-024-01165-5. → Beschreibt mitochondriale Dysfunktion, oxidativen Stress und therapeutische Ansätze

(60) Noonong et al. (2023): Mitochondrial oxidative stress storms in long COVID pathogenesis Frontiers in Immunology, 14:1275001 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1275001. → Belegt die Rolle von ROS-Stürmen, oxidativem Stress und mitochondrialer Belastung

(61) Komaroff & Lipkin (2022): Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: What Do We Know? PNAS, PMCID: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8723833. → Parallelen zwischen Long COVID und ME/CFS, inkl. Immun- und Energiestörungen

(61) García-García et al. (2021): SIRT1 and Metabolic Syndrome: A Review of Current Evidence International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(4), 1944 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22041944. → Relevanz von SIRT1, CYP2C19 und mitochondrialer Regulation

(62) Croci et al. (2022): The polymorphism L412F in TLR3 inhibits autophagy and is a marker of severe COVID-19 in males Autophagy, 18(7), 1662–1672 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2021.1995152. → Belegt die Rolle von TLR3-L412F bei gestörter Autophagie und Immunantwort

(63) Komaroff, A. L., & Lipkin, W. I. (2022). Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: What Do We Know? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) PMCID: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8723833., https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8723833. Die Arbeit beschreibt zentrale pathophysiologische Merkmale von ME/CFS, darunter Immunstörungen, mitochondriale Dysfunktion, oxidativen Stress und Parallelen zu Long COVID. Genetische Prädispositionen werden als relevante Forschungsrichtung genannt.

(64) IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans, Herausgeber: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), World Health Organizatio, https://monographs.iarc.who.int. Die IARC bewertet seit 1971 die Karzinogenität von über 1000 chemischen, biologischen und physikalischen Agenzien. In den Monographien wurden unter anderem folgende Stoffe als krebserzeugend eingestuft: PAKs (Polyzyklische aromatische Kohlenwasserstoffe) z. B. Benzo[a]pyren (Group 1), PCB (Polychlorierte Biphenyle) – Group 1, Dioxine (z. B. TCDD) – Group 1, Ionisierende Strahlung – Group 1, die Monographien enthalten auch Hinweise auf genetische Prädispositionen (z. B. BRCA1/2, TP53, CYP1A1) und metabolische Enzyme wie EPHX1, die die individuelle Karzinogenverarbeitung beeinflussen können

(65) NIOSH NMAM 2017 – Aniline, o-Toluidine, Nitrobenzene https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2003-154/pdfs/2017.pdf.

(66) SpringerLink – Nitrogen Compounds in Organic Chemistry https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-31458-2_3.

(67) PharmGKB – SULT1A1, UGT1A1, EPHX1 https://www.pharmgkb.org.

(68) United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2008): Chloropicrin: RED Factsheet U.S. EPA Office of Pesticide Programs, July 2008 https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/chem_search/reg_actions/reregistration/fs_PC-081501_10-Jul-08.pdf. → Dokumentiert zivilen Einsatz als Bodenbegasungsmittel, Wirkmechanismus und Umweltexposition

(69) U.S. EPA Acute Exposure Guideline Levels (AEGL) Program: Chloropicrin AEGL Summary Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Air and Radiation https://www.epa.gov/aegl/chloropicrin-results-aegl-program. → Enthält toxikologische Grenzwerte für Innenraumbelastung und Expositionsszenarien

(70) European Solvents Industry Group (ESIG) (2019): Indoor VOCs and legacy solvents in post-flood structures Branchenbericht zu Raumluftkontamination in Altgebäuden (Hinweis: ESIG-Dokumente erfordern Zugriff über Branchenserver oder ECHA-Datenbanken)

(71) Österreichische Agentur für Gesundheit und Ernährungssicherheit (AGES) (2022): Chlorierte Lösemittel – Bewertung in Innenräumen nach Wasserschaden AGES Toxikologie, Umweltmedizinischer Report Nr. 145/2022

(72) I-WASTE Decision Support Tool (EPA): Chemical Agent Profile – Chloropicrin Integrated Waste Decision Support Tool, Hazardous Waste Division https://iwaste.epa.gov/guidance/chemical-biological/agent-info?agent=chloropicrin. → Verbindung zwischen industrieller Nutzung und militärischer Relevanz, inklusive Abfallbehandlung und Schutzmaßnahmen

Dieser Beitrag wurde verfasst von Birgit Bortoluzzi, kreative Gründerin der „Universität der Hoffnung“ – einer unabhängigen Wissensplattform für Resilienz, Bildung und Mitgefühl in einer komplexen Welt.